|

Newcastle

was indisputably the heart of the mining community of the north-east,

its main arteries branching out into the neighbouring coal-seams of

Northumberland and Durham, fetching and carrying the ceaseless round

of coal.

Although it is no longer the staple industry of the area it has handed

down a firm tradition recorded in the many songs and poems of the miners

themselves.

Humour was a main feature of the earliest recorded songs, such as the

Collier's Rant (1784):

As

me an' me marra was gannin te work

We met wi' the divil, it was in the dark,

Aa up wi' me pick, it bein' the neet,

An'aa howked off his claws, likewise his clubfeet,

(chorus)

Follow the horses, Johnny me laddie

Follow them through, me canny lad oh

Follow the horses, Johnny me laddie

How lad, lie away me canny lad oh.

Yet it was a black, grim humour, no doubt a reaction against the inherent

hardships of mining. Other songs, not so harsh, originate from the pre-industrial

revolution era; for example, Byker Hill:

Geordie

Thompson had a pig

And he hit it with a shovel and it danced a jig

All the way to Byker Hill

It danced the Elsie Marley.

(Chorus)

Byker Hill and Walker Shore, me lads

Collier lads for evermore, me boys

Byker Hill and Walker Shore, me lads

Collier lads for evermore.

George Hitchin in his essay 'First Day' writes: "I tailed along

behind the men until we reached a point where the last electric light

glowed. Beyond lay utter darkness. The light of my lamp grew in brightness

in contrast to the enveloping gloom. We had been following a narrow

railway, but presently we turned off at an angle, leaving the railway

behind as we entered the travelling road or gallery. A hundred yards

or so along this road we stopped outside an iron gate, but not before

I had received my miner's baptism by knocking my head on the roof. Beyond

the gate, as in a corridor, were lights, voices, a jingle of harness,

the stamping of hooves and a strong smell of horse manure. Just inside

the stables stood the wagonway-man, talking to a youth, Gillie held

up his lamp to see my face.

"What's thou called, hinny?"

"Hitchin," I replied. "Geordie Hitchin."

"Sailor Hitchin's lad?" he inquired.

I admitted it, and he turned to the youth by his side. "Not very

big, is he?" They both laughed. "Gang we' Fred, here,"

he instructed me. "I'll see thee in-bye. And mind thou doesn't

fall in the greaser." He rumpled my hair with his hand."

The Industrial Revolution brought a greater demand for coal and conditions

deteriorated. The miner's voice became more embittered, e.g. Thomas

Wilson's 'The Pitman's Pay' 1826:

Think

on us hinnies, if ye please

An' it were but to show yor pity

For a' the toils and tears it gi'es

To warm the shins o' Lunnun city.

Militancy increased as the 19th century approached. Blacklegs were

brought in to break strikes, and the hatred this caused boiled over

into 'The Blackleg Miner':

Oh

early in the evenin' just after dark

The Blackleg miners creep out an' gan to work

Wi' their moleskin trousers an' dorty auld shirts

Go the dorty blackleg miners.

They

take their picks an' down they go

Te dig out the coal that's lyin' below

An' there isn't a woman in this town row

Will look at a blackleg miner.

Oh

Deleval is a terrible place

They rub wet clay in the blackleg's face

An' round the pit-heaps they run a foot-race

Wi' the dorty blackleg miners

Oh

divvent gan near the Seghill mine

For across the way they stretch a line

For te catch the throat an' break the spine

Of the dorty blackleg miner.

Ye

take yor duds an' tools as well

An' down ye go te the pit of hell

It's doon ye go an' fare the well

Thou dorty blackleg miner.

So

join the union while ye may

Don't ye wait till yer dyin' day

Fer that may not be so far away

Ye dorty blackleg miners.

In another song, the militant mood is reflected, this time against

the owners during the great ''lock-out' when miners protested about

a 10% pay reduction. The word 'candy' is used in the song. It originated

when a local candy-seller turned blackleg hirer in the early days of

north-east miners strikes. Afterwards blacklegs were called candy-men.

Oh

the miners of South Medomsley, they're gannin' to make some stew,

They're gannin' to boil fat Postick and his dorty Candy Crew,

The maisters shall have nowt but soup as long as the're alive

In mem'ry of the dorty trick in 1885.

Because of the conditions and lack of safety regulations disasters

were frequent. Tommy Armstrong's famous Trimdon Grange Explosion records

one such event.

Oh

let's not think of tomorrow lest we disappointed be

Our joys may turn to sorrows as we all may daily see

Today we're strong and healthy, but tomorrow brings a change

As we all may see from the explosion that's occurred at Trimdon Grange.

Men

and boys set out that morning for to earn their daily bread

Not thinking that by evening they'd be numbered with the dead

Lets think of Mrs Burnet once had sons but now has none

By the Trimdon Grange Explosion Joseph George and James have gone.

February

left behind it what will never be forgot

Weeping widows helpless children may be found in many a cot

They ask if father's left them an the mother hangs

With a weeping widows feelings tells the child its father's dead.

God

protect the lonely widow and raise up each drooping head

Be a father to the orphans do not let them cry for bread

Death will pay us all a visit they have only gone before

And we'll meet the Trimdon victims where explosions are no more

The tradition continues today with such men as the late Jack Elliott

of Birtley, and Johnny Handle.

The

collier lad, he's a canny lad,

And he's always of good chear

And he knaas how to work,

And he knaas how to shork

An' he knaas how to sup good beer.

Nowadays poets still write in appreciation of the miners' hard struggle.

For example, Robert Morgan wrote:

On

the way out, through twisting roads of rocky

Silence, you could sense images of confusion

In the slack chain of shadows; muscles

Were nerve tight and thoughts infested

With wrath and sharp edges of fear.

Towards the sun's lamp we moved, taking

Home the dark prisoner in his shroud of coats.

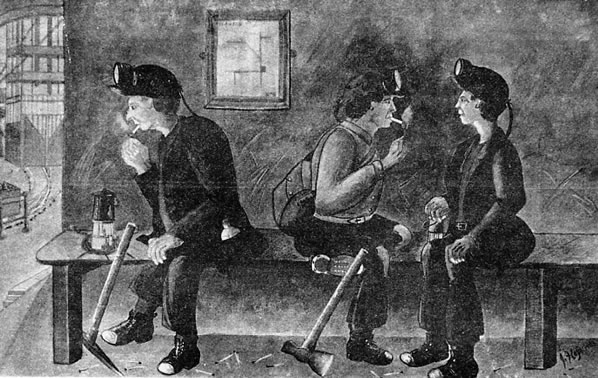

Jim and Geoff

'The Argument' by James Floyd - Ashington miner - by courtesy of the

DLI Museum

Many thanks to Joe Gott, steward of Bearpark Working Men's Club,

who has helped out immensely during the miners strike by laying on meals

at most mealtimes for the picketing miners. Ally, his wife, also took

rum down to the pickets to keep them warm. Apparently he has also helped

a lot of the miners financially. Keep it up Bruvvers!

|